Passio

An Interview with Paolo Cherchi Usai

Grant McDonald

|

Passio Grant McDonald |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

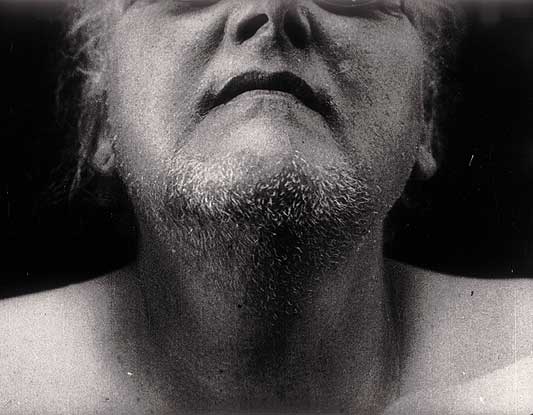

Rouge: The exact contents of Passio are, at this point, something of a mystery to us. What criteria or intuitions were you using when you gathered the various image-materials from the numerous archives? Paolo Cherchi Usai: Everything in the film reflects Arvo Pärt's music: my goal was to engage in a tightly knit dialogue between the sounds and the images, between each scene and each word of the text being sung by the soloists and the choir. Some correspondences between the visual and the aural component were immediately evident to me as I was recalling images I had already seen, and all I had to do was to retrieve them. In many cases I knew what I wanted to show in relation to a specific bar of the score, but I couldn't find the right kind of match: the shot was either too grainy or too sharp, too realistic or too abstract, too elliptical or too obvious, its inner tempo was too leisurely or too abrupt. I discarded some truly wonderful shots I had hoped to insert in the final cut just because they were not long enough, or because their beauty would distract the viewer from the essence of the musical experience. It sometimes took a very long time before I could find exactly what I wanted for a given phrase of the libretto. I struggled almost six years before deciding between two versions of the final shot I had at my disposal. I eventually made up my mind – it was the most difficult decision of all – but I have kept a copy of the abandoned version, just in case. R: Passio exists only in a film format. With the current obsession with DVD and owning a copy of a film, what motivated you to show this film only in its original format? PCU: To me, the choice of the material is always the first step in a new work. A carpenter chooses the type of wood to be used in making a chair. A musician decides whether a given piece should be for voices or instruments. I have chosen 35mm for Passio, as the film would not be what I intended it to look like in any other format. It just wouldn't work. I'd love to make something in digital form at some point. R: Several descriptions of Passio refer to the element of 'shock', alluding to the confronting nature of the some of the material you have chosen. What was your attitude to using such material that obviously has a certain 'spectacular' element – a kind of spectacularity that has often been abused in documentary and fiction cinema alike? PCU: I was determined from the start to avoid any form of gratuitous spectacle, and I stood by this resolution until the very end of the production process. The images themselves may be at times disturbing, but there's not a single frame of conventional violence in the film. This was my plan from the outset, and I made the point clear to Paul Hillier since the very beginning of the project. The music would not allow me to do otherwise, even if I had wanted to. What has been described as upsetting is – I think – the result of a different mental pattern. If I had edited those images in a conventional manner, they would be perceived as something not as confronting, certainly not as much as, say, what is seen in the latest work of Yervent Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi (which was being made while I was in postproduction). What makes people so uncomfortable comes perhaps from the way in which the scenes are juxtaposed within the film. There is nothing especially shocking about the images as such. Some people were so troubled by what they saw that they commented upon images which do not appear at all in the film. I find this interesting. R: Reading the various descriptions of Passio, we naturally think of other grand 'montage films' that provide some form of commentary on the twentieth century and its history: Godfrey Reggio's Koyanaiqaatsi and its sequels at one extreme, and Godard's Histoire(s) du cinema on the other. How did you approach the formal challenge of constructing such a work? PCU: Passio is a follow up to my book The Death of Cinema. I am increasingly dissatisfied with the question, ‘What do these images mean?’ I'd like to know more about the reasons why we want to produce and view artificial images at all; way too many of them, as it has now become clear. I have often argued that images do not demonstrate or prove anything at all; at best, they may achieve the status of symbols, something of much more enduring value than evidence or, worse, ‘content’. Images have nothing to explain; it is us who should explain ourselves to them, and justify the fact that we have made them exist. Mircea Eliade, Pavel Florenskij and Georges Bataille are among the few who have hinted, however remotely, at this kind of approach to the act of seeing. The fact that Eliade had done so within the framework of a study on the religious phenomenon hasn't made him very popular in this secular age, but one has to be able to discern what's potentially useful in a perspective we don't necessarily agree with. Religion does not have a monopoly over the ecstatic experience and while Passio is not exactly an ode to reason, it is also not a religious statement. I find it curious that some viewers felt the need to keep themselves at arm's length from the film just because they're sceptical about the theme of the music. You don't have to be religious to read the Bible. Gurdjieff’s Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson may or may not be the work of a charlatan, but it is nevertheless quite a compelling book. R: You have spoken of the 'tightly knit dialogue between the sounds and the images'. Many filmmakers down the decades have experimented with all the various relations of image-to-music: synchrony, asynchrony, illustration, counterpoint, etc. What kind of relations were you working with? PCU: In rhythmic terms, I obeyed the self-imposed rule of absolute synchrony with instrumental sounds and voices. I made an exception for the organ part, which often serves as a basso continuo in Pärt's score. In visual terms, the relationship is a blend of mental association and displacement. Enhancing emotion while deliberately staying out of context has been my mantra. Before inserting an image in correspondence of a character's part, I would ask myself, ‘Jesus, Pilate or Peter are now talking. What do they represent? How should I interpret what they are saying? Why are they emphasizing this or that word?’ Then I would respond to them in my own terms, often commenting upon or contradicting what they said. In a few cases I simply confirmed their viewpoint by illustrating its implications. The Evangelist's parts and the instrumental interludes required different approaches. I saw the role of instrumental interludes as something equivalent to the chorus in ancient Greek theatre. As for the Evangelist, he is the narrator – John, the author of the Gospel – and I dealt with him as such. Then there's the chorus of Pärt's score: in Passio – the music – I imagined the chorus as an antiphonal voice, the response of a crowd to an unfolding drama. In the film, the chorus is the audience responding to what they hear and see. The English word, ‘audience’, derives from the Latin word ‘audire’, which stands for ‘to listen’. In the English-speaking world, the term refers to those who listen, watch, witness. This identity is not reflected in the French, Spanish and Italian languages, where another Latin word – ‘publicum’, a collective body – is the root of the corresponding words for ‘audience’. R: Yuri Tsivian has spoken of the 'written words that refuse to be read' in Passio. How is the calligraphy of Brody Neuenschwander incorporated into Passio? PCU: Brody wrote his calligraphy directly onto the film stock. The written word appears in correspondence with the parts sung by the Evangelist. R: Each of the seven prints of Passio has been handcoloured a particular colour. Could you describe the technical process of handcolouring each print and how colour is used in the various images you have chosen? PCU: Brody soon realised that the aniline dyes commonly used for film handcolouring in the early twentieth century are no longer commercially available. After some search, we settled for a special kind of dyes used for still photography. They all worked beautifully, with the kind of luminescence and transparency I was looking for. Each print has a specific dominant hue, and the brushstrokes were applied to different shots in each print, based on the correspondence between colours and images in the film. As a result, the seven prints are very different from each other. Only the last shot was handcoloured in all the seven prints. R: Much of your work and reflection has been on the theme of the 'death of cinema'. With Passio, we learn that you have destroyed the original negative and left only the seven prints. Is this because you wanted to craft a wilfully 'ephemeral' film-object? Do you think you will ever regret the decision or gesture to destroy the negative? PCU: I like to treat my film as a biological entity. The prints have been deposited, donated or bequested to archives and museums around the world, with the legally stipulated proviso that the film will not be reproduced in any form nor projected with a recorded soundtrack. I hope they will abide to my wishes, but even if they don't, the reproductions will not be handcoloured prints. The decision to destroy the negative was made back in 2000, when I started the project, so I had plenty of time to get used to the idea. Still, the destruction of the negative was a very emotional moment, something like the ritual slaughter of an animal. I saw one in Central Asia and was struck by the depth of the feelings attached to the gesture. Passio is screening at the Adelaide Film Festival, 23 February 2007. |

|

© Paolo Cherchi Usai and Rouge January 2007. Cannot be reprinted without permission of the author and editors. |

|||