The Secret Life of Objects

Mark Rappaport

|

The Secret Life of Objects |

|||

|

|

In their heyday, all of the major studios and even some of the minor ones had backlots. Very often, on the backlot – which included acres of land used in Westerns or outdoor country scenes – they built a small nineteenth-century town standing set, with houses and an old-fashioned town square, as well as a semi-permanent Western set. The larger studios had standing urban street sets which would they would use if the movie was set in the streets of New York or Chicago or Boston. Since they shot so many films, these sets were permanent fixtures and lowered the overhead of building each location from scratch for every new film. Some studios, like MGM, even had a permanent swimming pool – seen in The Philadelphia Story (1940) and, then, for its many Esther Williams films. MGM even had their ‘elaborate ballroom set’, with its distinctive and immediately recognisable floor. This was invariably used in many, many MGM films over the years, regardless of who the director was, primarily in period movies when they needed to simulate a royal court, a lavish hotel, a fancy mansion, a chateau, and so on. Even if you never noticed it, you probably did notice it, unconsciously. Or noticed it and then forgot about it. It appears in film after film, And, of course, once you really notice it, you can’t stop noticing it. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Three Musketeers (1949) MGM |

|

|

Moonfleet (1955) MGM |

|

|

The Great Sinner (1949) MGM |

|

|

We like to call the movie studios dream factories, but only part of that phrase is accurate. If the dream part is arguable, the factory part is not. Everything that was used could conceivably be re-used. And sometimes the way it was re-used is much more extravagant and imaginative than the use to which it was originally put. For example, MGM again – nineteenth-century London street sets were built for Albert Lewin’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1944) and, even though we do not get to see very much of them in the film, from an existing still we can see that there was much more set than we view in the finished film. This very same set was used again, to much greater effect, in the spectacular ‘Limehouse Blues’ number in Minnelli’s Ziegfeld Follies (1946). An interesting question for those of us who find themselves interested in this kind of nuts-and-bolts, Marxist approach to film history to consider – was the ‘Limehouse Blues’ number designed around the already-existing set because the set ‘inspired’ it, or was Minnelli specifically instructed to find ways to use the already pre-existing sets to incorporate them into the number, thereby getting the most use out of a clearly expensive set? |

|

|

|

|

|

The Picture of Dorian Gray (1944) MGM |

|

|

Scene from Dorian Gray not in the film |

|

|

It should come as no great surprise to anyone that Minnelli’s use of the same space is much more architectural, three-dimensional, and cinematic than Lewin’s. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ziegfeld Follies (1946) MGM, shot on the same sets as Dorian Gray (1944) |

|

|

The movie business has always been a business like any other, and even more so than most. Every dollar counted and every penny had to show up on the screen. To put it another, blunter way – it was very likely, as a cost-saving device, an economic imperative to utilise to the fullest every board, plank and canvas flat on the studio stages. Sets and parts of sets would get recycled, with lower-budgeted films probably benefiting the most from the cast-offs of the major productions, although even major productions cannibalised sets and parts of sets, architectural trim, chandeliers, wall sconces, sections of staircases, doorways, etc. from other films. Consider this example: George Sidney’s Scaramouche was released in the US in May 1952. Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful, which was shot between April and June 1952, was released in December 1952. A left-over section of one of Scaramouche’s most elaborate set pieces, the duel in the theatre, is used as a throwaway in Minnelli’s film. The partial set is not necessary for the short twenty-second, single-shot scene in The Bad and the Beautiful, in which Kirk Douglas rehearses with Lana Turner – but it certainly enhances it. |

|

Scaramouche (1952) MGM |

The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) MGM |

|

|

The set, clearly kept in mothballs for future use, resurfaces for a cameo appearance in Minnelli’s Two Weeks in Another Town, ten years later in 1962, with added-on opera box modules. This time, Kirk Douglas is rehearsing Rosanna Schiaffino. Is it the same ladder? |

|

|

Two Weeks in Another Town (1962) MGM |

|

|

Also in The Bad and the Beautiful, on what is presumably a naked sound stage, Minnelli makes a witty allusion to the fancy MGM flooring, a standard fixture in their costume dramas. |

|

|

The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) MGM |

|

|

Sometimes a set is so striking, making such an indelible impression, that you cannot forget it. For example, the courtroom set at the end of Leave Her to Heaven (1945) is so foregrounded that I immediately recognised it, while dial-flipping, in 20th Century Fox’s The Black Swan, made three years earlier in 1942, also serving as a courtroom, but with palm trees outside the attention-getting oeil de boeuf windows. Incidentally, or not so incidentally, the cameraman on both films was Leon Shamroy. (Note well: The back walls, of both sets, which contain the windows, are rounded.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If Chinese restaurants leave no part of the pig and the chicken unused, the same might be said of the studios and the props they used. Every studio had a prop warehouse where they would keep the many props and furnishings they owned. Let us imagine warehouses as big, and as crammed with junk, as well as a few stray treasures, as those housing the trophies of Charles Foster Kane’s manic buying sprees, seen at the end of Citizen Kane (1941). In fact, there is a scene in The Bad and the Beautiful in which Douglas takes Dick Powell and Gloria Grahame on a tour of the prop warehouse. Grahame sees the perfect dining room table and (as unlikely as it may be) complete with chairs, already set with silverware and china and floral arrangements, for a scene of a film adaptation of Powell’s novel. Several scenes later, when they shoot the movie in question, it is being used exactly as we previously saw it. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) MGM – before and after. |

|

|

It is fun to imagine movie studios being as profligate in their spending as sultans in Arabian Nights fantasies, but absurd to imagine that every movie made was propped from scratch and that every set was decorated without resorting to the vast resources of objects that the studio already owned. Why would one? Most props are semi-invisible. They give the necessary detail to a background so that a room does not feel empty, so that it seems lived in. In addition to which, photographed from different angles, with different lenses, lit differently and in a new setting, they are usually unrecognisable. They blend in with the surroundings because they are not perceived in the same way as they were in a previous incarnation. It is not expected that the viewer will examine every cranny of every frame, pay attention to every sofa, chair, and table setting, examine the design and fabric of the drapes. The viewer’s job, assuming that he has one other than enjoying the film, is to pay his/her admission and then, hopefully, pay attention to the story and the actors. Viewers are not supposed to concern themselves with the ever-shifting landscape of details in the background. That is the set decorator’s job. Art directors, set directors, prop masters probably all had encyclopaedic memories of the treasures stored in their warehouses. Their jobs were to dress sets on budget or even below and make them look as expensive as possible. Saving money and creatively re-using items that were in storage was part of the job. |

|

|

The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) MGM Kirk Douglas (left) and Barry Sullivan (center) trying out various staircases from the studio’s warehouse. |

|

|

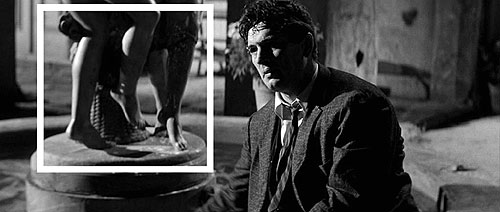

But, of course, there are movie hounds whose eyes are always grazing all over the frame, especially if it is a movie we know well or by a director we love or a movie that we have seen over and over again. Sometimes connections are made quite by accident. You notice a table lamp. Didn’t I see a lamp very similar to that in another film? I probably did, but I cannot remember in which film. And then you turn on the TV, and there it is – in another film. Sometimes there are personal reasons for making the connections. One sees a film and one cannot, for whatever reason, forget a prop, or an artifact, or a doodad. And then one sees the same object in another film, made of course, by the same studio, from the same vintage. And sometimes props call attention to themselves – either by their extravagance or the singularity of their appearance. When studios made their films in the ‘40s and ‘50s, they were made as disposable commodities. They never expected audiences to see them more than once and certainly not to remember details from the films years later. In fact, films were so disposable that almost all the copies were destroyed after they had played all the theatres where they could be played, in order to reclaim the valuable silver nitrate used in film stocks’ emulsion. The studios understood the financial benefits of a certain kind of ecology and re-cycling long before the rest of us would. Studios never dreamed that there would be a category of moviegoer, sometimes called cinephiles (sometimes called worse things), who would see the same film or films over and over again. Nor did they dream that cable TV would situate various different movies from the same studios in random juxtapositions so that viewers decades later could see connections between the films that were invisible to viewers at the time. Similarly, no one could even imagine, although certainly cinephiles may have had amorphous, unarticulated dreams of as-yet uninvented inventions like the VCR and DVD, which would make movies available in ways that they never had been before. The ability to compare and contrast and even describe in detail specific aspects of movies has always had pitfalls for those writing about film because of our faulty or imprecise memories of them. In this respect, the VCR and now the DVD player is an invaluable tool in scholarship, analysis, and even enjoyment. Speaking for myself, although I have a fairly good memory, I certainly do not have a photographic one. The availability of films on DVD enables me to make connections I never made before. Similarly, access to VCR and videocassettes gave me the idea and encouraged me to make several films in which scenes from various movies that were never intended to be seen in juxtaposition to each other, could, through the magic of current-day technologies, find themselves cheek to jowl with one another in unholy and previously undreamed of combinations. At one point, I started to make compendium film about the representation of art and artists in Hollywood films. It was to have been called Art is Just a Guy’s Name, after Rock Hudson’s retort to Otto Kruger’s inquiry in Magnificent Obsession (1954), as to whether Hudson had any interest in art. ‘As far as I’m concerned, Art is just a guy’s name’. It was to have included some of my favorite art-related lines in the movies; from An Affair to Remember (1957) and also Love Affair (1939) on which it is based, both made and re-made by Leo McCarey, the nuttiest line ever – Deborah Kerr, paralysed for life, saying to Cary Grant, who had always wanted to be a painter, ‘If you can paint, I can walk!’ uttered without a trace of irony. (When Irene Dunne says the same exact same thing to Charles Boyer in the 1939 version, he actually flinches when she says it, uncertain as to the exact intention of her remark.) Another favourite is Joan Bennett, in Lang’s Scarlet Street (1944). Wiggling her bare toes at Edward G. Robinson, she says, ‘You’re a painter. Paint them!’ And then adds as a somewhat vicious afterthought in her inimitable Joan Bennett-drawl, at once taunting and bored to death, ‘They’ll be mahsterpieces’. The reason I mention this partially-edited, never-completed film is because there were scenes in it from The Dark Corner (1946), a very interesting, largely-forgotten noir by Henry Hathaway, in which Clifton Webb plays an art dealer. Unlike most art dealers in real life who seem to specialise in one or two areas, he has a huge gallery filled with tons of sculptures and paintings (from the 20th Century Fox prop rooms, no doubt) from almost every period imaginable, including a Vermeer, a patently fake Raphael, and tons of Chinese ceramics. One sculpture caught my eye. When you’re going back and forth editing various scenes, seeing the same footage over and over again, you develop a familiarity with the material you not would ordinarily have. Objects which are placed in a scene just to fill up space, begin to assume an importance they were never meant to have. One of the sculptures that populate Webb’s gallery I subsequently recognised in a publicity still – another use for the items in the prop warehouses – taken by George Hurrell in 1944 of Gene Tierney, a Fox star. It is also used in a casual tracking shot, as incidental art in a well-appointed apartment in Julien Duvivier’s Tales of Manhattan (1942), also a Fox film, a portmanteau movie tracing the history of a tuxedo jacket as it passes from one star-filled vignette to another. |

|

photo of Gene Tierney, a Fox star, taken by George Hurrell in 1944. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Dark Corner (1946) 20th Century Fox |

|

|

The male companion to this sculpture can also be briefly glimpsed in The Dark Corner gallery. |

|

|

|

|

|

But it comes into its own several years later, when we can get a really good look at it, however briefly, as a prop on a roof terrace, in Cinemascope. |

|

How to Marry a Millionaire (1953) 20th Century |

The Dark Corner--detail |

|

|

To make a full-fledged, all-out study of this – the appearance of parts of sets, the re-use of props in studio films would not only be a sign of madness but would probably lead to madness, as well. One could, for example, look through all the available (and that, I suppose, is the operative word), let us say, period movies made by 20th Century Fox over the course of a handful of years, or all of MGM period movies to discover bits of sets, sofas, fireplaces, mantelpieces, doors, window casements, lamps, etc. But to what purpose? We already know that it was a common practice to recycle, aside from the scripts, various elements of productions. But sometimes the choices are surprising. We are all familiar with the signature portrait of Gene Tierney as Laura in Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944). Originally, Preminger commissioned an artist to paint her portrait but was not satisfied with the results. Instead, he had her pose for a photo shoot and had the photo touched up to look like a painting. Some very resourceful art director or set decorator, when they were shooting On the Riviera (1951) with Tierney, remembering Laura, decided to use the portrait to decorate the villa she lives in with her husband, one of the two Danny Kaye’s. We are so used to seeing it in black and white, it is quite a shock to see it in colour; it seems a little vulgar, too. |

|

|

|

|

Laura (1944) 20th Century Fox |

|

|

|

|

On the Riviera (1951) 20th Century Fox |

|

It seems that the same photo of Tierney is also used in Jean Negulesco’s Woman’s World (1954), as part of Clifton Webb’s collection of photo portraits of previous conquests, clearly another in-joke for the cognoscenti –and the art department at 20th Century Fox. One could certainly say they got their money’s worth on this particular prop. And, speaking of On the Riviera and of The Dark Corner, there’s an unusual, and very ungainly, prop that’s seen very briefly in Webb’s palatial house, skulking on the staircase landing. Five years later, the whatever-it-is has a fresh coat of paint on it with gold highlights and reappears in On the Riviera, separating the two Danny Kaye’s from each other. |

|

The Dark Corner (1946) 20th Century Fox |

On the Riviera (1951) 20th Century Fox |

|

We shall probably never know for sure how many guest appearances it made between those two films. However, I happened to catch Henry Hathaway’s vastly entertaining Seven Thieves (1960), also by 20th Century Fox. Guess what you can see in the background of the Monte Carlo casino, the location for the movie’s big heist? The very same thing – and its equally ugly twin – in the distance. |

|

Seven Thieves (1960) 20th Century Fox |

|

Anyone interested in trying to track down sightings of the chandeliers and wall sconces is on their own. As for the columns, I would suggest, for openers, starting with Fox’s own The Robe (1953) and Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954). Very recently, I re-saw Mankiewicz’s underrated Five Fingers (1951), every bit the equal of his highly-respected masterpieces like The Barefoot Contessa (1954), All About Eve (1950) and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1944) – and, voilà, there they are again – the two things, silently guarding the entrance to the hideaway James Mason has rented, for clandestine and nefarious business reasons, for Danielle Darrieux. |

|

Five Fingers (1951) 20 Century Fox |

|

Another discovery, quite by accident: mirrors used in two different 20th Century Fox films, in rather well-known scenes in well-known films, are actually the same mirror. |

|

All About Eve (1950) 20th Century Fox |

|

How to Marry a Millionaire (1953) 20th Century Fox |

|

And still another discovery – once you start paying attention to these things, you discover them everywhere – a statue once used in Song of Love (1947) is splashed with a coat of paint to look like it is made of malachite, in Minnelli’s The Bandwagon (1953). Everything gets used, including the beak, claws and tail. |

|

Song of Love (1947) MGM |

The Bandwagon (1953) MGM |

|

|

|

|

The last of the examples is the most serendipitous of them all. A friend gave me a gift of a boxed set of lesser-known and mostly lousy Rock Hudson titles, one of which was Douglas Sirk’s Has Anybody Seen My Gal? (1952). In it there is a statue in the house that the nouveau-riche family acquires. It looked strangely familiar, although I could not quite place it. In Sirk’s Written on the Wind (1956), a film I know very well, there’s a very peculiar statue that’s seen very fleetingly in the lobby of the Miami hotel to which Robert Stack first takes Lauren Bacall. Could it be ... ? What if the statue in Has Anybody Seen My Gal? ... ? I could hardly wait to check out the Written on the Wind DVD to see if the sculptures in the two different films matched. Bingo! They are one and the same. |

|

Has Anybody Seen My Gal? (1952) Universal |

Reverse angle — Written on the Wind (1956) Universal |

|

Now here’s where the real serendipity really comes in: the very same week I made that discovery, there was an article in the New York Times heralding the re-opening of the newly renovated Detroit Institute of Art, including a photo of one of its more precious acquisitions, a sculpture by Giovanni Maria Benzoni, made in 1867, called ‘Zehpyr Dancing with Flora’. The statue gathering dust in the Universal-International prop storage, waiting until someone could find an occasion to use it, was a copy or another version of a sculpture that, at one time, was more prestigious and more highly-regarded than it is now. |

|

|

|

The same sculpture, sans pedestal, can be glimpsed briefly, if only barely, in a night-time scene as part of a fountain in Sirk’s The Tarnished Angels (1958). |

|

|

|

The Tarnished Angels (1958) Universal |

|

Speaking of Written on the Wind, in another shot in the same Miami hotel, and speaking of Benzoni – whom I frankly had never heard of before – we can catch a glimpse, ever so briefly, of another one of his sculptures at the end of a corridor. The same sculpture turns up in the Alte Nationalgalerie in East Berlin in Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain (1966). The ‘museum’ was recreated, mostly with background plates, on the Universal backlot. The sculpture, ‘Cupid and Psyche’ by Benzoni, clearly from their storerooms, was added to spruce things up a bit. Evidently, the Universal art department picked up a couple of Benzoni’s at a two-for-one auction. |

|

Written on the Wind (1956) Universal |

detail |

|

Subsequent to writing the bulk of this article, I saw De Palma’s Scarface (1983), also by Universal, on TV. I was vindicated at the end because there they were, briefly-seen, bit players in the big shoot-out at Pacino’s mansion-cum-brothel: both ‘Cupid and Psyche’ and ‘Zephyr Dancing with Flora’. There’s little doubt that, over the long haul, Universal got its money’s worth from these two acquisitions. I wonder, however, if De Palma, who made his career by pillaging and cannibalising Hitchcock, knew or knows the illustrious resumés and antecedents that these props have, and what a soft spot in his heart Sirk had for them. |

|

|

|

Scarface (1983) Universal |

|

Final entry on Benzoni. Just the other night, I saw again, for the first time in a very long time, Ophuls’ sublime Letter From an Unknown Woman (1948), made at Universal. Here is the earliest of the Benzoni sightings, although I would be reluctant to swear to it. To put it another way, the prop had gotten ample use as a resident artifact at Universal Studios, without even taking into consideration its very likely guest appearances in Universal’s TV movies and series. |

|

Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948) Universal |

|

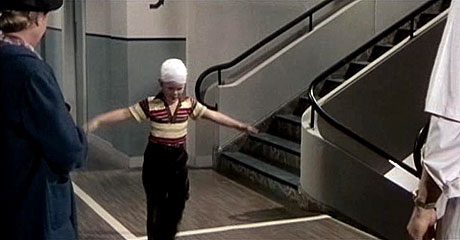

Also noticed, in Has Anybody Seen My Gal? is a stairwell in a courthouse. The same stairwell appears in Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession, two years later, this time as part of a hospital set. This ‘location’, flexible and ready to be changed for whatever the script might require, just needing a minimal bit of set dressing, was most likely a functioning building on the Universal lot. |

|

|

|

|

Has Anybody Seen My Gal? (1952) Universal |

|

Magnificent Obsession (1954) Universal |

|

It does duty, once again, in Sirk’s Imitation of Life (1959), this time as Sarah Jane’s school, but minus the handrail on the banister. |

|

Imitation of Life (1959) Universal |

|

It is an aspect of movies we do not think about too often – or do not want to think about. We want (or, perhaps it would be better to put this in the past tense: wanted) the film to cast its magic spell. We want/wanted to be swept away by the illusion of the illusion. We do not want to be reminded that it was a cost-conscious business like any other business – in which expenditures had to be kept down and every nickel accounted for. We do not want the magic taken away. We do not want to see the Marxist underpinnings of each scene as it unfolds – unless iit is by Straub-Huillet or Godard – complete with a cost accounting at the right hand bottom of the screen, like a taxi metre run amok, ticking, ticking, ticking, indicating the costs of building each set, the costs of the fabrics, the furniture, each individual prop, where it was bought or how much it cost to make it. We want the illusion preserved. Keep the dream and throw away the facts. Just as we do not want to know that that most delightful of movies, Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967) was the most expensive French movie made at that point, that the cost overruns bankrupted Tati, forced him to give up the rights to his previous films, and severely curtailed his subsequent ability to make movies. So, what does all this tell us that we do not already know? We know that even although Hollywood studios lavishly threw money at their productions, at the same time, the studio heads and the producers were also penny pinchers. Every penny was carefully watched and accounted for. If they seemed to be creating magic for their audiences, it was probably a less magical experience for the film workers themselves, including the actors, who would trudge to the same sound stages in film after film, with the lighting and the sets and the props being re-arranged, seemingly transforming a familiar environment into what was meant to be a brand new location. And for us viewers willing to believe that the transformation was complete, sometimes an unidentifiable prop that may seem like we’ve seen it before, or a familiar looking piece of furniture that we can’t quite place, the films with their sometimes interchangeable parts, provided the feeling of a dream or a sensation of déjà vu which may have all too well been true. The sad but also wonderful thing about this knowledge is that it really doesn’t demystify the movies, but only makes them seem more mysterious and unknowable, not more artificial but more densely textured, than ever – their histories even more complex and convoluted than we imagined, with even more cross-hatched and interlocking connections. There are movies, of course, in which props figure prominently, where they are part of the fabric of the plot – like the earrings in Ophuls’ Madame d The Earrings of Mme De ... (1953) or the ever-moving rifle in Anthony Mann’s Winchester ’73 (1950). Or the wooden-handled jump rope in Buñuel’s Viridiana (1961) that starts out as the plaything of the young girl on Don Jaime’s hacienda and ends up as the belt of Viridiana’s would-be rapist. In these films, the props come to mean something much larger and more important than what they actually are. They become metaphors for the social, psychological and emotional situations they passively and unwittingly participate in. They become encrusted with layers of meaning as they diagram a cumulative network of relationships and plot complications around themselves and become imbued with a fetishistic meaning beyond that which the plot accords them. They wind up containing the plot even though they are not the plot. In a way, they all become the tuxedo jacket that passes from hand to hand in Tales of Manhattan (1942), bearing witness to many lives and many stories. But these are extraordinary cases in the history of props. Most props do not have it so good. But maybe that's not entirely true. Cocteau, as usual, may have said it best in his diary kept during the making of Beauty and the Beast (1946), writing about the still extraordinary effect of the human faces encased in the architectural details flanking the fireplace in the Beast's palace. |

1. Jean Cocteau (trans. Ronald Duncan), Beauty and the Beast: Diary of a Film (New York: Dover, 1972), p. 101. |

These heads are alive, they look, they breathe smoke from their nostrils, they turn, they follow the movements of the artists, who don't see them. Perhaps this is how the objects which surround us behave, taking advantage of our habit of believing them to be immobile. (1) |

|

So let us imagine another scenario: the secret lives of objects. What the contents in the refrigerator talk about, as they sometimes do in cartoons, and in TV commercials, when the refrigerator door is closed, the lights are off, and the owners of the house are not around. What do the props in the prop shop say to each other about the movies they were in once the doors are closed? The fictitious lives of objects that only exist to perpetuate other fictions as they get recycled from movie to movie. They all have tags, detailing their histories and their provenances – which movies they were in, how close they were to the camera, how prominent in the frame, how long they were on screen. They compare notes, they tell each other stories about the hilarious and awful things that happened on their sets. They gossip about the stars and the directors. They brag to one another about their pedigrees and credits, their shining moments, and their favourite films. Which actors they liked working with, who were the best cameramen and lighting technicians, the times they were almost dropped and smashed to smithereens, or overlooked completely. Apartments and sets I appeared in and which famous actors and actresses fondled me, or manhandled me, or glanced admiringly at me, or ignored me completely. Although it is possible, just possible, that objects are not nearly as starstruck or as impressed with Hollywood movies as the rest of us are. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

© Mark Rappaport and Rouge April 2009. Cannot be reprinted without permission of the author and editors. |

|||