Dziga

Vertov: Kiev 1 Sept[ember] [19]28: Storyboard

Roland Fischer-Briand

|

Dziga

Vertov: Kiev 1 Sept[ember] [19]28: Storyboard |

|||

|

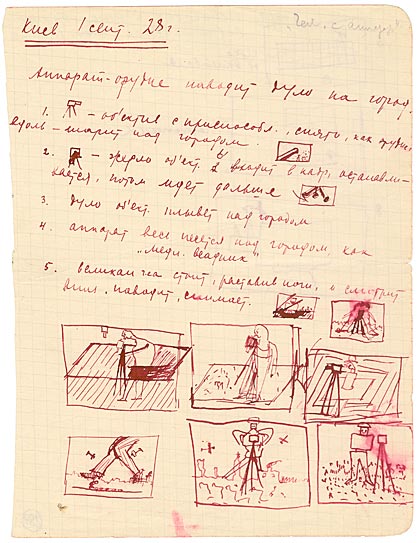

Gun apparatus directs

its muzzle towards the city. 1. [Camera] lens with a device, filmed like a gun, lengthways – moves tentatively over the city. 2. [Camera] muzzle of the lens enters the picture, stays still and then wanders on 3. Muzzle of the lens hovers over the city 4. Camera races across the city, like the ‘Bronze Horseman’ 5. Giant C c.s.a. [C Celovek s kinoapparatom = man with the camera] stands straddle-legged, stares downwards, takes aim and starts to shoot.

|

|

|

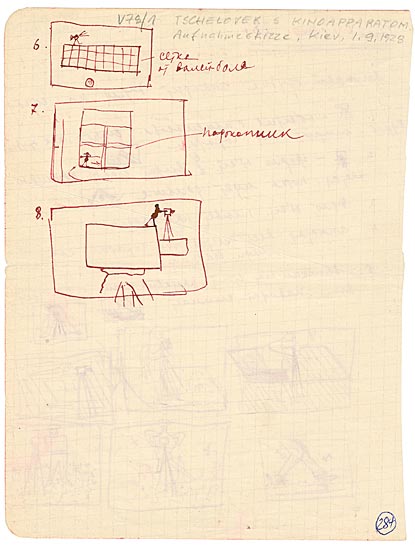

6. -- Volleyball net

7. ----------- Window-sill

|

|

|

|

Score of vision In several respects, this dated page, which has been cleanly torn out of a grey notebook with squared paper, constitutes a remarkable document deriving from Vertov’s red pen. To date, no comparable example is known in which the glowing champion of documentary film made a preparatory list of camera shots, picture contents and compositions and extensively commented upon them. Although it is not a storyboard in the strict sense – since it does not present a cohesive sequence – the document does give us an idea of the relationship between the plan and its implementation. In the first place, the text is impressive on account of its resolute, almost energetic tone. This results from the aggressive vocabulary used. The contraction of syntax and rigorous economy in the use of lettering testifies to Vertov’s adherence to the principle of efficiency. The individual sentences and fragments of sentences are often put together from abbreviations of words and in fact even the film title itself, C Celovek s kinoapparatom, becomes the acronym ‘C c.s.a.’. At the same time, by making a reference to Alexander Pushkin’s Mednyj vsadnik [‘The Bronze Horseman’], Vertov was able to evoke the whole drama of a historical verse epic. Even at the top of this page, some notions are immediately visualised by means of a small line drawing. One should notice the difference between the words ‘camera lens’ (point 1), which are drawn in profile, as in a pictogram, and the ‘camera muzzle’ (point 2), additionally emphasised, which targets the viewer directly. While the visual elements are at first still integrated into the lines of text or at least match the format of the line spacing, in point 5 they continue to develop until the language of the words is replaced by that of the images. In the final emblem (point 8) this culminates in a complete shift away from the written word and towards the visual idea. Here, quite without captions, what has been created is more or less an iconogram for the phrase ‘first Russian film without intertitles’. In going beyond the frame, the camera tripod here builds a bridge between the world of the frame to be projected and the real world of the filmmaker. As in the film itself, the self-referential circle between production and reception has been brought to a close. This preparatory sketch arose during shooting, as a set of definite instructions for Vertov’s brother Michail Kaufman, the film’s hero and cinematographer. Apart from the precise of movements of the on-screen camera, it also visually develops concepts for multiple exposures, i.e. montage in the frame. Some of them can be immediately recognised in the film – e.g. those for points 2 and 8 (cf. the frame enlargements from the film). Others can be derived from the text, such as the analogy with a giant or with Pushkin’s hovering and all-seeing horseman. More abstract visual concepts, such as the fusion of operator and apparatus may also be identified. The head becomes the doppelganger of the camera housing, with a nose in the form of a lens. In a further drawing, the borders blur between the legs of the hero and those of the tripod. Body and camera merge and determine each other. The lens itself is infrequently directed towards the protagonists and in several frames one may notice a certain tendency towards symmetry and consequently towards what can be controlled and overseen. In the midst of the aeroplanes that are flying around, the arms are raised like wings. Next to them, the torso is brought into harmony with the body of the camera. Vertov’s associations were also incorporated into the poster by the Stenberg brothers. While movement is indicated by means of arrows, pin stripes (trouser legs) or factory smoke, there are some frames which are more difficult to interpret. These include the three sketches in which the floor (the world as seen from the ‘Giant’s’ perspective) is filmed. When examined more closely, they literally topple over and out of the vertical level of the two-dimensional drawing. As in a picture puzzle, the man with the camera here seems to be standing on firm ground, yet the back wall seems to fold backwards and literally surround him. |

|

| frame enlargements: Georg Wasner, Oesterreichisches Filmmuseum |

Two

frames further on, the protagonist finally appears to slip through the

folded down space (radial arrow!) and be circumscribed by it, while his

attribute, the camera, is able to move freely between them. The detached

gaze. Or as Vertov himself put it:

|

|

My film therefore

signifies

|

from Österreichisches Filmmuseum, Thomas Tode, Barbara Wurm, eds., Dziga Vertov: The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum (Vienna: FilmmuseumSynemaPublikationen, 2006) |

|

© Roland Fischer-Briand and the Austrian Film Museum 2006. Cannot be reprinted without permission of the author and editors. |

|||